Working on a piece such as MANAHATTA is definitively a challenging feat. Set in 1600s Manahatta and 2008s New York City and Anadarko, Oklahoma, Ty Defoe manages to go back and forth in time and space while gracefully guiding actors and encouraging an appreciation of each other’s creative process. It is a demanding yet unique exercise that requires a comprehension of the different eras. But how has Defoe’s background informed the production?

Jesús Garibay: Ty, you are such a multifaceted artist and you have exercised your craft through so many different mediums. Is there something that you bring with you from “home”?

Ty Defoe: I think that as an Indigenous artist, I'm bringing the sensation of “thriving” in the place and the people I am with at the moment. I’m interested in both interpersonal connections and artmaking because I know they can be of service to the greater world when both converge. For me, art is connecting the past, present, and future because I grew up in Wisconsin, which has this beautiful and amazing culture. At the same time, I found this sense of theatricality and drama that plays into family dynamics. I'm also trying to navigate how to walk in a duality of worlds that include my movement vocabulary and the language of Mary Kathryn Nagle because, as an Indigenous artist, I’m looking to recover that sovereignty in my body, spaces that I occupy, and the way I dialogue with other people. That sovereignty is very much being created for MANAHATTA from a place of what I bring from home.

Garibay: How much of your own need for bringing your ancestors before you plays consciously in your work for MANAHATTA?

Defoe: I love that question because this idea of our ancestors' past brings us to this present moment. It's literally why we are here. We are creating the work as individuals who have an evocative past and, hopefully, future generations will have this feeling of hope and aliveness when remembering their ancestors. Thinking about MANAHATTA in particular, which is a story of people from the Lenapehoking nation, these people are beautifully related to my own since we are from the same language-speaking group and have similar frameworks and concepts in our relationships. We have this moment in the play in which a group of rocks, from our Indigenous viewpoint, are not just rocks, they are our relatives. They are our brothers, sisters, mothers, and fathers, and the spirit that lives through them can inform and evoke how we show up in space. I mention this because there is something very real and authentic in the perception and tools that we are now using to present a Native play. After all, I, as an Indigenous-identifying person, can set up some sort of Easter eggs that maybe some people will catch and if you are an Indigenous person, you will identify this authenticity. And even if you’re not Indigenous, you will feel and see something thanks to the blend of Indigenous culture and rituals with what theatermaking is.

Garibay: Speaking of that blend, what research do you conduct to make the movements seem as seamless as possible? How do these movements inform the already challenging setting of the play?

Defoe: For me, being the Movement Director, I try to embody the nonverbal. I’m looking for the layer that I believe lives just beneath the text and by looking at that layer we find a map that guides us to a specific dramatic moment. When we then find that moment, we start working with more cultural imagery such as the Medicine Wheel, the Seven Generations Breathwork, and bodywork so that actors can widen themselves up and be able to open their chest and their shoulders to then face the audience while looking at them and start speaking the words on the page. I see it as Narrative Medicine, and it becomes really important when I think about movement direction. We have also been making use of Indigenous handspeak, which is something that has been documented as preceding American Sign Language. This handtalk wasn't necessarily even in English and yet it served as a way of trading food, shelter, and clothing, even with non-Indigenous people. We can only imagine it as a whole system created to bring nations, communities, and tribes together and still being so open to interpretation because it’s the language of the body, a language of proximity. This is, in a way, the language that we are using to amplify, elevate, and recapitulate in this story of MANAHATTA.

Garibay: How do you usually find the movement of a piece? Is there something that you are usually looking for?

Defoe: I love music so much! Whatever that means at the moment, you know? Like the sound of the breeze, birds in the morning, Beyoncé! Even the way people speak, because I think there's a certain kind of tempo to it and I feel that I can hear it, so in MANAHATTA, I try to really listen to the language that Mary Kathryn wrote. I try to gather all this data from the page and try to focus on how the actors are interpreting the language, so I'm able to orchestrate all these things that are happening at the moment. Sometimes, they can be incongruous and we need to really focus on the drama of the scene and in other moments it just happens beautifully and it all comes together with the flow of the handspeak or the movement on stage.

Garibay: How much of a challenge has it been guiding the actors through two completely different time frames and spaces?

Defoe: There are a lot of emotional containers that have been made, and many permissions have been granted for our actors to reign over the space that they are taking at the moment because of the difference in authority and autonomy in both time frames. When we talk about Indigenous people and their stories, how much of it are we able to recognize and recall? When they are able to connect the language on the page, their thoughts, and their bodies it is nothing short of magical. This is something that everyone in the room is capable of feeling.

Garibay: Is it rewarding to be present for those moments? Do you feel accomplished? What part of you becomes healed? Since you’ve mentioned Medicine a couple of times…

Defoe: Oh my gosh, it's such a precious moment. Mary Kathryn has crafted this beautiful story that clearly reveals Lenape women and it is so specific that it immediately becomes universal. In those moments I think about little details, I think about my mother and my sisters, that even though they're not Lenape, by telling this story we are also dispelling myths and untruths that have followed us for centuries. The healing begins at the moment when we are in the rehearsal room and we dare to ask questions like “OK, but what is really happening here?” or “How was being traded for X amount of knives and guns right at the moment?” and so on. At the same time, we come to conclusions that actually bring us laughter. Because we have to come into the same room as Native and non-Native people and say “Ok, now what?”, and we laugh because at the end of the day, what are we really doing here? And also, the audience. Healing is happening in front of them because there's no way to escape the truth that is happening before their eyes when we talk about the invisibilization of Indigenous people, the missing and murder of Indigenous women. Human rights like this have been overlooked for so long and it's wonderful that a heartfelt play like MANAHATTA can really be this meaningful. Which, in the end, is the genesis of art. At least that's why I make art—art that speaks to the people—because we need to have that change. Even if it changes two people in the back row. Or maybe just one student who will be encouraged to make their own work. That's the most important thing about this.

Garibay: Is that what happened to you, were you that student?

Defoe: Yes, it's now their turn to start building their own legacy (Laughs to himself)

MANAHATTA runs through December 23, 2023. To purchase tickets, click here.

Jesús Garibay is a Mexican actor with a passion for expansion and growth. His enthusiasm for theater goes beyond his fervor for the stage and has now evolved into an amplification of other people's voices. You can find Jesús on both IG and X as @jesusmgaribay.

This piece was developed with the BIPOC Critics Lab, a new program founded by Jose Solís training the next generation of BIPOC journalists. Follow on X: @BIPOCCriticsLab.

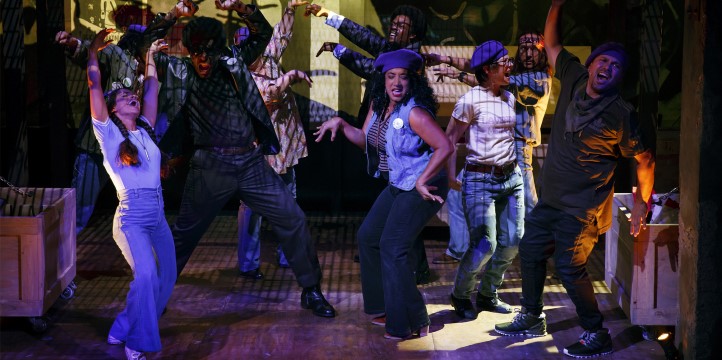

PHOTO: Jeffrey King, Elizabeth Frances, and Joe Tapper in MANAHATTA. Photo Credit: Joan Marcus.