What Richard II Said to Shakespeare’s Audience

By Ambereen Dadabhoy, Assistant Professor of Literature, Harvey Mudd College

William Shakespeare’s Richard II (1595) offers a majestically poetic meditation on power, monarchy, rule, and misrule. Inaugurating Shakespeare’s second tetralogy of English history plays, Richard II depicts the events that led up to that king’s deposition by his cousin, Henry Bolingbroke, and unsettled the foundations of the English monarchy, eventually resulting in the Wars of the Roses. The play ruminates on the obligations and duties inherent in political power, on the honors and obeisance owed to the monarch, and the reciprocal protections and care offered by the monarch to the people.

When Shakespeare began writing Richard II, England was in a state of political uncertainty and instability. This last decade of Queen Elizabeth I’s reign was troubled by several poor policy decisions, including the queen generating revenue by leasing royal land, a disastrous foreign campaign in Ireland, and anxiety in the populace over the future of the nation because of the queen’s unmarried and childless state. This final point was perhaps the most relevant to Richard II, because the queen’s death threatened to push the realm into the kind of civil conflict the play depicts.

The queen, it seems, was aware of the connection between her rule and that of her medieval counterpart, declaring at one time, “I am Richard II, know ye not that?” This remark, which might be apocryphal, also points to the power of Shakespeare’s own rendition of this story in his play. In 1601, the Earl of Essex attempted a rebellion against the queen, and on the eve of that rebellion, he and his co-conspirators commissioned a performance of Richard II that included the deposition scene in Act 4, which had previously been excised from productions. The performance was meant to inspire the conspirators, who saw themselves in the roles of Bolingbroke and his triumphant allies. This plot, however, failed and Essex was executed. Nonetheless, the queen and Shakespeare’s audience understood the moral of his play: that power is fleeting and that the performance of power must be accompanied by material physical strength as well as the support of the people.

What Richard II Says to Audiences Today

By Ruben Espinosa, Associate Professor of English, University of Texas at El Paso

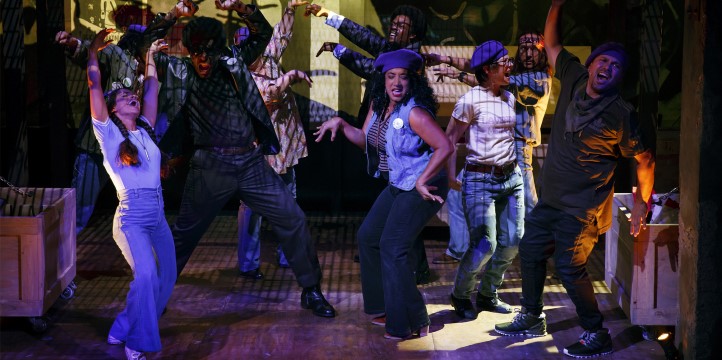

In Richard II, corruption, vanity, and the undeniable threat of tyranny are on full display. Because the play was written and staged during a period when England was under monarchical rule, it would be easy to suggest Richard registers fears that are comfortably couched in the historical past of Shakespeare’s England. They are not. Corruption, vanity, and tyranny at the highest level of government loom large in our present moment.

Beyond that, though, Richard’s specific attention to and defense of birthright also haunts us now. The fundamental belief that one is born into a position of privilege and power is not only relevant to the nobility within Richard and Shakespeare’s England, but directly correlates to views of white supremacy in our own world. Who inherits particular rights, property, and power in our day? What systems of power have enabled that? At what cost are such systems of power preserved? Today, we must interrogate such views of privilege and power in order to resist and dismantle racist paradigms and threats of tyranny.

Indeed, while the play depicts, through Richard and those who flatter him, the widespread effects of corrupt government, the nobility backing Henry Bolingbroke are also deeply invested in preserving their own positions of privilege and power through their own corrupt means. For audiences, then, Richard not only illustrates the perverse power of the state, but also that corrupt and violent power demands resistance and even revolt. For many now who are for the first time coming to terms with the violent and racist history of this nation, Richard suggests that looking head on at such perverse power is not enough if, like Bolingbroke, we seek to wash the blood from off our nation’s guilty hands.