A conversation with Greig Sargeant and John Collins of Elevator Repair Service, about how BALDWIN AND BUCKLEY AT CAMBRIDGE came to be, and the relevance of the 1965 debate today.

By the time James Baldwin arrived at Cambridge University in 1965 to debate the proposition: “the American dream is at the expense of the American Negro,” the house had long since been corroded. Its ceilings were infested and in dire need of attention, the walls were tarred black, and its very foundations lay precarious. What was clear then, and what holds true today, is that America has a problem. Standing in opposition to William F. Buckley, Jr. (a man described as “possibly being the most articulate conservative in the United States”), Baldwin justifiably delivered a withering critique of this country. His words at Cambridge revered him as one of the world’s foremost social critics. It was the meeting of two opposites and it was the essential reckoning with place and pretence that Baldwin had addressed in previous works such as “Living and Growing in a White World.” Through Elevator Repair Service’s re-imagining of the conversation, we’re invited to pick up the baton and re-build the house once more.

The original 1965 debate has been preserved online and is available to stream. Baldwin actor Greig Sargeant notes that, for him, while the experience of being a Black gay man in the context of America has been in some senses a profoundly alienating one, accessing those archives was a liberating undertaking. For him, researching this project was a form of grounding. As he views things, the same injustices exist in our culture today just as they did when Baldwin made his appearance in 1965. Through the process of finding Baldwin and bringing him to the stage, Sargeant asks: “What are we to do about them?” The urgency of that proposition was articulated by Baldwin, then, too. In the opening of his address, he describes a realization that every Black American soon comes to: that “the flag, to which you have pledged allegiance along with everybody else has not pledged allegiance to you.”

BALDWIN AND BUCKLEY AT CAMBRIDGE is as unembellished as the suit Baldwin himself wore to attend his engagement at Cambridge University that day. Working on this project together, Elevator Repair Service director John Collins and Sargeant deliberated intensely in the lead up of its live premiere on how best to retain the essence of the conversation and on the importance of letting the words of Baldwin lead. “Fundamentally things haven’t changed [as they relate to] race,” Sargeant says. “I could see myself having this conversation now.” Indeed, in thinking about ways to move through the COVID-19 pandemic and at a time when the political climate was as emotionally charged as ever, they wanted to find ways to transpose his words into the present, almost as a way of providing some clarity in the murkiness of the socio-political waters. Chiming in, Collins reminds us how “[over] the last couple of years, people really began to see this conversation as urgent. We thought about doing it online but we had to bide our time and see how we could make it come alive.”

Of course, while the moving parts of this play were coming together and as Collins and Sargeant worked alongside one another to think of a way to present the work, they were in the midst of contemporary debates on race in America and the legacy of slavery. The analyses of power, patriation for the American Negro, and who is in the position to give it (at the time of the debate and now), is something that BALDWIN AND BUCKLEY... seeks to investigate. In response to Robert F. Kennedy’s statement that “it was conceivable that, in forty years in America, we might have a Negro president,” Baldwin sardonically shoots back “he tells us that maybe in forty years, if you’re good, we may let you become president.” For Collins and Sargeant, the show's concept felt timely not just in terms of the racial climate within which it was conceived but because such a conversation would ultimately spur further dialogue. Art-making was the connective tissue to that stream of critical consciousness. “John and I, we belong to a race of artists,” says Sargeant. “This was a way of continuing a wider conversation in order to deliver it to a new generation of people who will imagine newer, better ways for us to live.”

Ultimately, BALDWIN AND BUCKLEY... is in equal measures reflective as it is prospective: a theme that runs throughout. And Elevator Repair Service was keen to play with those ideas of temporality. On the decision to conclude the piece with an imagined conversation between Baldwin and Lorraine Hansberry as a conclusion, Sargeant notes that “We didn’t want Buckley to have the last word.” With that final concluding statement from Buckley, which is met with an ovation from the audience, the vigour of the debate is offset sweetly by the two artist friends seated together in a living room. “They were friends, they were artists and they would get together in each other’s homes [to] drink, smoke and exchange ideas,” Sargeant describes. “When we think about James Baldwin, we see the public persona and we never [get to] see the private persona. Here we decided we wanted to investigate the private relationship between the two of them, as well as show another side to him, to this, and to the debate.” After all the talk of power among men, among the walls of institution, the deeply intimate ending to the production leaves us not deprived of intellectual rigour, it affords us with more. More to ponder, and more to consider. Cajoling one another—and at moments in a vernacular seemingly only Baldwin and Hansberry know and could understand—they meditate finally on what progress could look like for the American Negro.

Vuyokazi Mtukela is a writer based in the North West of England. You can follow them on Twitter @vuyomtukela.

This piece was developed with the BIPOC Critics Lab, a new program founded by Jose Solís training the next generation of BIPOC journalists. Follow on Twitter: @BIPOCCriticsLab.

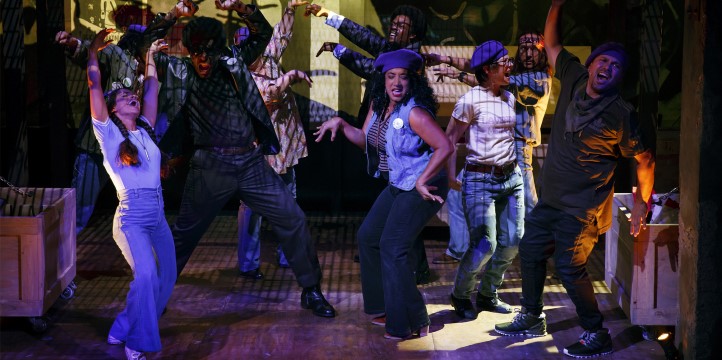

PHOTO: Greig Sargeant as James Baldwin; photo by Joan Marcus