Writer Rishi Mutalik speaks with THE CHINESE LADY's Playwright Lloyd Suh and Director Ralph B. Peña about how the play has changed throughout its iterations and the importance of the current production, produced by Ma-Yi Theater Company and presented by The Public Theater.

There are moments in Asian American history that haunt Lloyd Suh. When the playwright discovers these moments, he gives himself permission to process their gravity. “Sometimes I'm like, ‘This is very painful stuff. Why am I choosing to sit with this?’” says Suh.

This was how Suh felt when he first read about Afong Moy, a figure many believe to be the first Chinese woman to set foot in America. In 1834, 14-year-old Moy was brought to New York by American traders and was soon “displayed” in a touring exhibition. In this exhibition, patrons paid to watch her eat, walk around with her bound feet, and speak through a translator. This performance was part of a marketing scheme concocted to sell Chinese goods to Westerners. It gave its spectators obscene permission to gaze upon Moy as if she were a cultural artifact: a dehumanized object that existed solely for their perverse curiosity.

Upon discovering Afong Moy, Suh felt the need to delve deeper into her story, if only to better understand what she experienced. It wasn’t until he immersed himself in his research that Suh considered the story’s theatrical potential. He thought about the weight of performing one’s identity while navigating expectations around that performance: a consideration artists of color know well.

“It felt inherently theatrical,” says Suh, "I thought if I’m going to wrestle with this, it makes sense to do it as a play and to do it in a way where I can get peers in a room with me.” This exploration soon became THE CHINESE LADY, a play that centers the voice and spirit of Afong Moy. In Suh’s piece, the actress embodying Moy speaks directly to the audience from within her exhibition panel, relaying her thoughts and curiosities as she travels to many cities over time. She is aided by a Chinese translator named Atung.

In writing THE CHINESE LADY, Suh had to grapple with conveying interiority for a woman whose perspective was never recorded. Additionally, he had to confront the fact that Moy vanished from all records after 1850. “I started to think about why history lost track of her and what it meant that people stopped caring, “ explains Suh. “Once I started thinking about that absence—that's what haunted me more.”

Informed by this impulse, Suh decided to conjure Moy through empathetic imagination, rather than historical accuracy. His piece is skillfully conscious of the distance between the Afong Moy of the play and the Afong Moy who actually existed, building that gap into the narrative. Through these choices, Suh allows Moy to transcend the very history that neglected her.

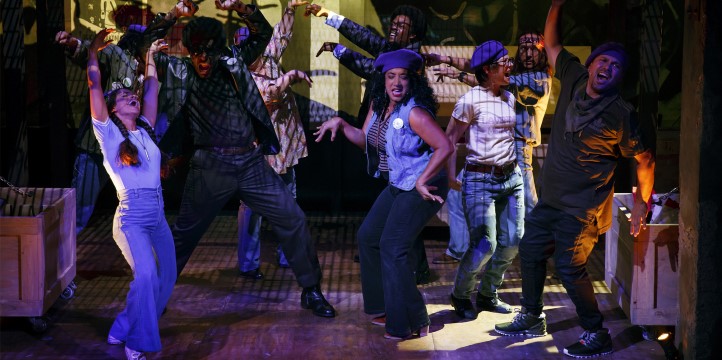

Since premiering in 2018, THE CHINESE LADY has been remounted several times, including an acclaimed run at Beckett Theater (Theater Row) by the Ma-Yi Theater Company. Four years later, the play makes its Public Theater debut, produced by Ma-Yi once again. For this production, Suh reunites with the play’s original director, Ralph B. Peña. When Peña first read Suh’s play, he admired its ambition. He had previously researched the people exhibitions at the 1904 World Fair, and recognized a throughline from Moy to that history.

“[These exhibitions] were a reinforcement of American superiority," says Peña, "It was fun for me to take on this play, which returns that gaze.” Peña also felt activated by Suh’s choice to forgo historical authenticity. “That opened up a world of possibility in terms of approach—visual, textual, and performative. It liberated everybody.”

Having worked on several plays together, Suh and Peña bring a history of collaboration to their work. “There are shortcuts that are already in place that make it very easy,” Peña says. Among these shortcuts is straightforward communication about what a play needs. Suh adds, “we’re always pretty honest about where we are, what we’re worried about, and what we’re feeling good about. ''

Instead of maintaining a fixed approach, Peña and Suh vary their process depending on the specific demands of the piece at hand. In the case of THE CHINESE LADY, the collaboration involves everyone, especially the actors. “We’re all Asian American and we bring these experiences to the play,” notes Peña. “We all have experienced being othered. We’ve all had to perform our ethnicities.” Thus, Peña creates a rehearsal room where all collaborators have authorship. The result is a production rich in subtext and interpretation, where the identities of the performers resonate just as sharply as the figures they are embodying.

The numerous runs of the play have only deepened this quality. With every mounting, Suh and Peña have returned to the work with a more expansive understanding of the piece’s possibilities. “It’s a good mark of a play that it's an onion that you can peel,” says Peña. “Every time, a new door has opened.”

The play has also been continually imbued with new context. As they revisit it once more, Suh and Peña are aware of the specific resonances the play has in 2022. With massive spikes in violence against Asian Americans, the dark histories at the center of THE CHINESE LADY hit viscerally and wrenchingly.

“The audience brings that with them,” explains Peña. “Whatever your relationship to it: whether you experience it, whether you know someone who has experienced it, or are far removed from it, you know about it. And that brings something to how you experience this play. “

Still, considering THE CHINESE LADY examines the violence of American colonization and racial capitalism, it is hard to imagine a world in which the play does not feel of the times. This is a testament both to how rigorously the piece is in conversation with the real world and to the craft of Suh's writing. “With everything I write, especially as I get older, I try to leave as much room as possible,” Suh explains. “I try to be very specific about the things I want to be specific about but if I don't need to be specific, I like to leave it as open as possible. Then the play becomes portable across time and space.”

THE CHINESE LADY is now playing at The Public Theater through Sunday, April 10.

Rishi Mutalik is an actor, singer, and writer based in New York City. He has performed at numerous theatrical institutions including Lincoln Center, Manhattan Theater Club, and Yale Repertory Theater. He is also the co-author of the play Color Coded. You can follow him on Twitter @RishiMutalik and subscribe to his newsletter, Sages and Stages.

This piece was developed with the BIPOC Critics Lab, a new program founded by Jose Solís training the next generation of BIPOC journalists. Follow on Twitter: @BIPOCCriticsLab.