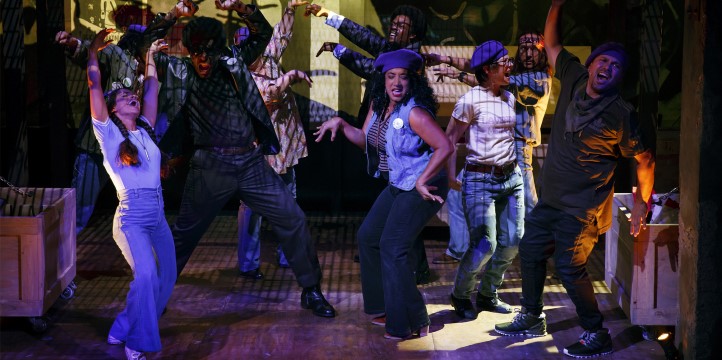

China meets America and a play meets a musical in David Henry Hwang and Jeanine Tesori’s SOFT POWER, which examines American ideology and dramatizes how art can advance political agenda. The co-commission between The Public Theater and Center Theatre Group makes its New York premiere at The Public this fall. Theater arts writer Yan Chen speaks with playwright and lyricist David Henry Hwang.

Yan Chen: The term “soft power” comes from international relations, and refers to persuasive, cultural influence as opposed to military or economic “hard power.” Why this title?

David Henry Hwang: The show, to a large extent, is about what "soft power" means, and how art and culture advance an ideological agenda. Because I've done a certain amount of work in China, and Chinese producers have approached me about projects, I've always wondered to what extent China's desire to achieve "soft power" is contradictory to its desire to control content. In other words, can cultural products that come out of a culture in which there's censorship achieve international success?

Chen: Why is the show subtitled "a musical within a play"?

Hwang: Another impetus for the show was seeing the most recent revival of The King and I at Lincoln Center. The King and I is a musical that I've always really loved, and this was a glorious production. I also was much more conscious, this time, of the things in the show that felt questionable to me, starting with the premise. There's such a trope in the West where the one white person in any country becomes the advisor to the ruler of that country. There's the reality of what actually happened, but then it gets blown up by the time the Western person writes the memoir. In Soft Power, you see the reality of a glancing encounter between a Chinese national and an American leader, and then, when it becomes a musical, you’d see the way that it has been mythologized.

Chen: How have you and Jeanine Tesori, who wrote the music and additional lyrics for Soft Power, dealt with the challenges in style and form that Soft Power’s unique, genre-straddling structure presents?

Hwang: The biggest challenge is tone, which has been an ongoing adjustment. In some sense, what we're trying to do is create a distancing lens through which we watch a musical. And yet, the musical itself has to be as effective and seductive and skilled as The King and I—I think we'd never get that skilled, but that's the goal. The very first draft was much more satirical, but we've become increasingly attracted to making something that feels sincere, in the way that a Rodgers and Hammerstein musical feels sincere, even though we, the audience, have a frame on it that allows us to see it through a more rigorous lens.

Chen: Soft Power depicts events in America during and after the 2016 election. Have ongoing current events contributed to changes in the show, and if so, how?

Hwang: The first draft was more analogous to The King and I, because my assumption was that Hillary Clinton would be President. In the original draft, Xue Xing, the Chinese national, would help President Clinton solve the problem of gun violence in America.

We had a reading of that script on Election Day 2016. I woke up the next morning, and thought, I think this election is bad for the country, but it could be good for our show. I think the real-life event allowed us to dig more deeply into the whole question of whether American liberal democracy was a blip in history, is it a good system, and how can it deliver what I believe to be nonsensical results. Since 2016, I don't feel like there's anything that's happened that’s contradicted the premise of the show.

Chen: Speaking of U.S.-China relations, how have the shifting political and cultural relationships between the two countries influenced your writing throughout your career?

Hwang: When I first started writing plays in my early twenties, I was fundamentally concerned with what it meant to be Chinese American and Asian American. Starting with M. Butterfly, my work started to go on two tracks: there was the Asian American stuff, like Yellowface, and the international stuff, like Chinglish.

This show brings together the international and domestic strains of my work. It is both an international tale and an attempt to acknowledge the ways in which the musical is a product of a Chinese American mind. One of the ways it does that is trying to locate the anxiety about the U.S.-China relationship in something more personal—the fear of persecution and racism here at home.

As a dramaturg and translator, Yan Chen has worked on productions and developed work at the American Repertory Theater, the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre, the Kennedy Center, Hartford Stage, Harvard University Theater, Dance & Media, the Chinese Universities Shakespeare Festival and more. Her writings and translations have appeared in publications including Playbill, Howlround, Critical Stages/Scènes critiques, and Stage and Screen Reviews (China). She studied arts criticism as a Fellow at the Eugene O’Neill Theater Center’s National Critics Institute and volunteers as Transcultural Collaborations Editor at TheTheatreTimes.com, a global theatre news platform. Born and raised in China, Yan received her theatre education in China, the US, the UK, Russia, and Poland. She holds a BA in English (2016) from Nanjing University in China and a Master’s in Dramaturgy (2018) from the A.R.T./MXAT Institute for Advanced Theater Training at Harvard University. In October 2019, she will be pursuing a Master’s in Comparative Literature and Critical Translation at the University of Oxford as one of four 2019 Rhodes Scholars for China. She believes in fostering international exchange, transcultural collaborations, and civic engagement through the arts, and aims to make the arts more affordable and accessible for a wider range of audiences. @chenultyan